A movie review is a critical appraisal of a particular film. A good review should entertain, persuade, and inform readers by providing an opinion. With the help of our movie review writing service, you can learn how to write one and get a high grade.

When you say write a book report for me, you may not know what to expect in most cases. Professional assistance is the key to succeeding in any college task.

CustomWriting.com hires qualified writers who help to complete college papers and bring students top grades. Apply for help with your movie review writing and get an experienced team of writers, editors, and proofreaders working on the project.

Can you write my movie review for me? Yes, this service offers you help, and we promise to complete your task on time. We will help you choose an expert writer who specializes in creating critiques. Next, give us your requirements and instructions, and watch the writing process unfold. Your task is safe with us!

Why You Should Choose CustomWriting.com

We write movie reviews for money, and we do it in the best way. Reliable service with years of experience, success, and positive customer feedback makes us the right place for your project. There are more than 200 writers and 12 top authors to choose from.

We apply a comprehensive approach to research, using plagiarism-checking software, double-checking for mistakes, and delivering on time. Find a book report helper by rating or evaluation, give your instructions, and watch the writing process online.

Pay when the project is completed and delivered. Revisions are free and included in the order. We stick to the customer’s requirements and never miss deadlines. Rely on us when a paper has to be completed overnight. We never let our customers down.

We provide a list of features, like one-page abstracts, essay outlines, and VIP support to suit your needs. We also offer various citation and formatting styles. All deadlines are met by our expert writers, so don’t worry about us turning in your paper late.

Our talented and experienced writers complete up to 150 tasks a day for new and regular customers, meeting all of their requirements and deadlines.

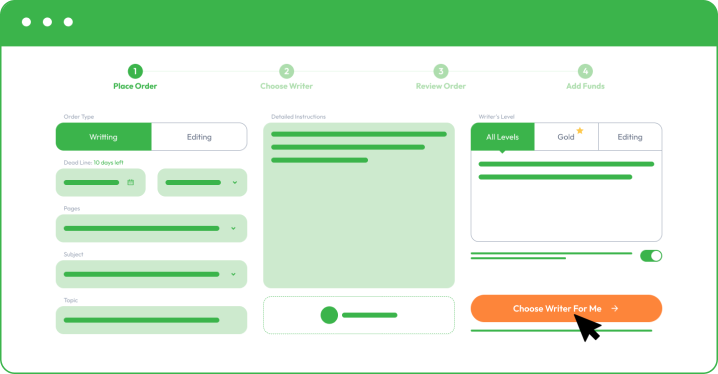

Contact us through our “order now” feature, tell us your requirements, and pick a deadline. Chat with our authors and select the one whom you think will do your task the best.

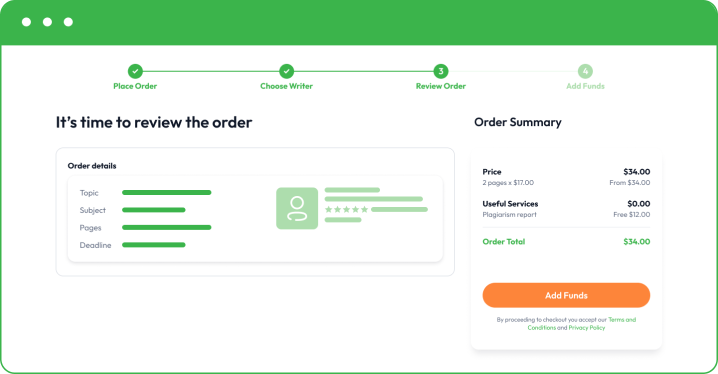

Make a deposit, and our author will write your essay. Send the whole amount of money only after checking the paper to make sure it meets your expectations.

Review the Benefits you Will Get

- Quality Assurance. We follow your requirements and stick to the highest educational standards to provide top-quality papers.

- Confidentiality Policy. No one will find out that you ordered our services. Your privacy is our priority.

- Affordable Prices. Enjoy fair rates and order any type of academic assignment when you have no time, or find a task too complicated.

- Experienced Writers. Our experts in academic writing provide excellent papers on any discipline and topic.

- 24/7 Customer Support. Contact our service and get information on any issue for free.

- Money-Back Guarantee. If you are not satisfied with the result, or the deadline is missed, we will return your money.

- Chat directly with our writers. Follow the writing process, give instructions, and stay informed about the order by chatting with the author.

- Custom Writing check paper for plagiarism. We deliver 100% unique papers that bring high grades.

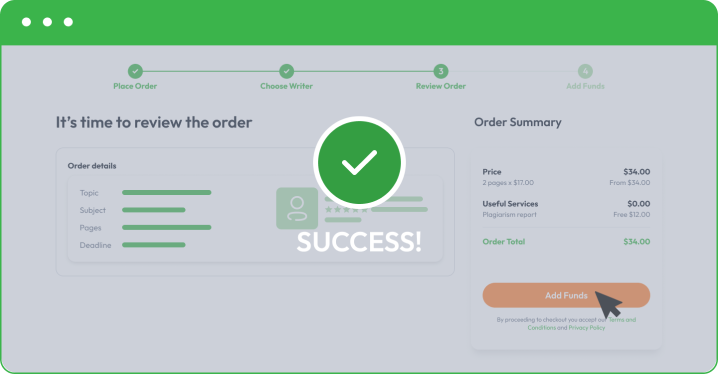

Choose customwriting.com and get success. Academic papers and tight deadlines don’t seem so scary when you have a team of professionals on your side. Take advantage of custom-writing essay reviews, and receive a paper free of plagiarism and mistakes.

Relax and get a perfect assignment written for you. Buy a movie review or any type of college paper online and receive an A+!

EduReviewer

EduReviewer